words and photos by Shab Ferdowsi

I met Cinna Peyghamy backstage at La Bellevilloise in Paris in March. It was a Disco Tehran party for Nowruz (the Persian New Year) where I was snapping photos and Cinna was opening the night with an experimental electronic tombak performance.

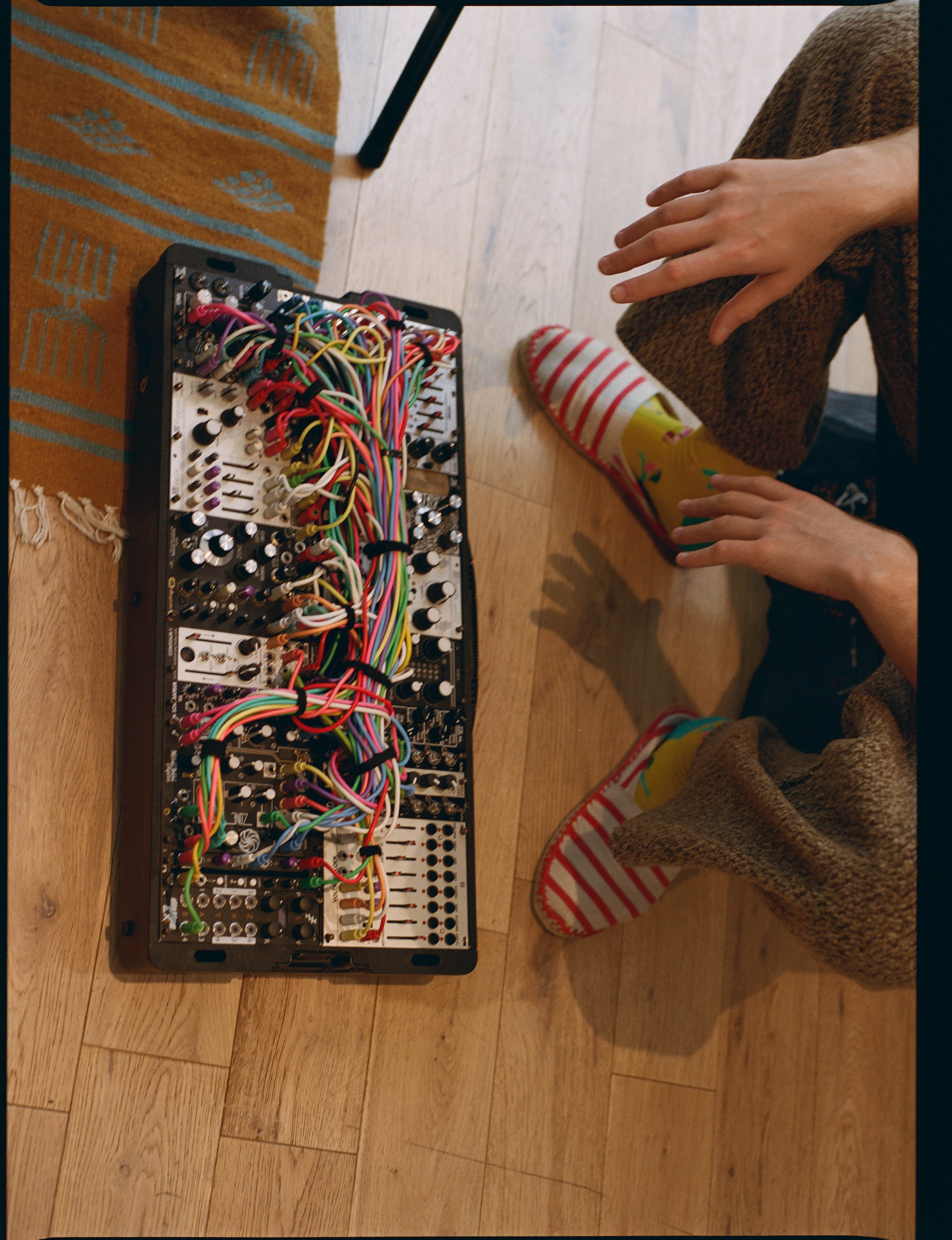

The room had just started filling up when Cinna took his seat on the small Persian carpet where his modular synth was set up on stage. He kicked off his shoes, placed his tombak (the traditional Persian goblet drum) onto his lap, and began. The crowd matched the energy by dropping down onto the venue floor, cross-legged and mesmerized, as Cinna filtered the sounds of his drum through his synth. Traditional sounds of the tombak turned into electronic waves and bytes, and by the end, I was hooked.

Backstage after the set, we were caught in a flurry of conversations with the other Iranian and middle eastern artists and event crew, speaking in French, and English and tossing in some Farsi here and there.

When I learned that Cinna, who was born in Paris to Iranian parents, had never been to Iran himself, I knew I wanted to learn more. How did he get here, mixing the sounds of a traditional Iranian instrument (which he mastered so well) with modern experimental playfulness?

A few weeks later I walked into his studio in the 20eme arrondissement on a rainy day. I grabbed a seat on the couch while Cinna poured me some tea and brought out a tray of Persian chickpea cookies called nokhodchi, the kind I ate every year during our new year growing up. I took a sip, grabbed a sweet, and listened.

Cinna was born and raised in Paris in a diverse neighborhood to Iranian parents. His passion for music started similarly to most other musicians. Guitar classes at a young age, a rock band with his friends, a pivot to playing drums, some Blink 182 covers, and many battle of the bands concerts at historic local venues like Bataclan and New Morning.

But where his journey starts to set him apart and on the path toward the cultural mélange of music he is making now started with his curiosity for electronics. His interest in making beats and learning about computers led him to a hybrid Engineering / Music degree in Paris. He was simultaneously on a science track at one school and a creative track at another learning how to code (DAWS, plugins, apps) while starting to perform his electronic sets on the side.

While feeling slightly uninspired by the drums, he fell onto a video of a Mohammad Reza Mortazavi, one of the best Iranian tombak players in the world, and was sold. This became his next pivot, and luckily he was able to start learning immediately thanks to a family friend who was an instructor in Paris.

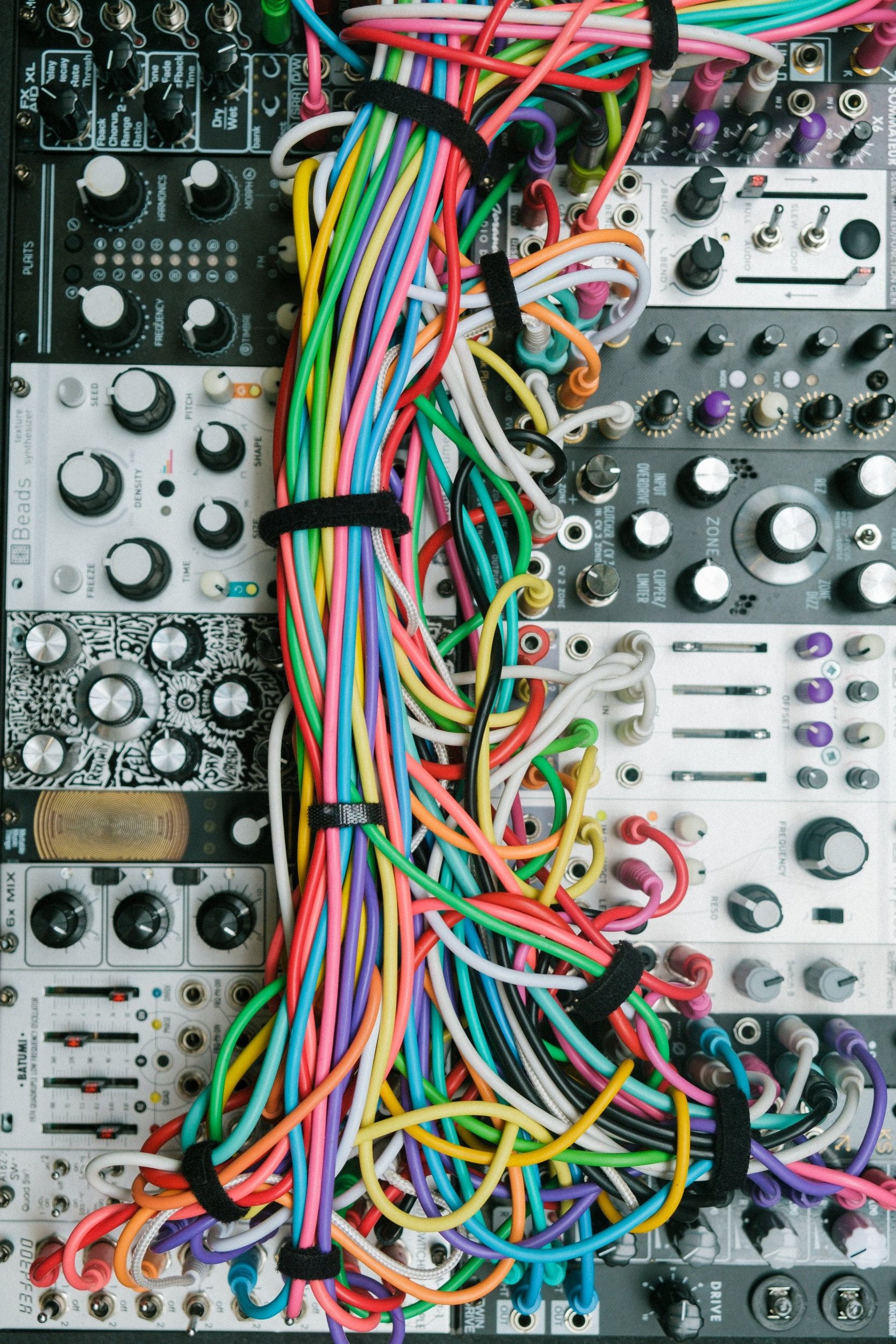

At the same time, he discovered the modular synth and began toying with the idea of combining the two instruments. As Cinna pulled out his synth board to explain to me how it worked and what all the colorful cables did (which I was somewhat able to grasp?), I began to see the dots starting to connect.

The synth and the tombak together create one single ecosystem, and Cinna’s performance becomes a musical manifestation of his exploration of his own cross-cultural identity.

At 25 he had what he called a “raise of consciousness” about his Persianness, where he became curious about his own heritage especially since he had never been to Iran himself. The tombak allowed him to connect with his parents’ homeland and the culture he had grown up with in his home. His practice has become a platform that helps him seek solace between his two worlds: France, a modern West where he was born and raised, and Iran, where he has his roots.